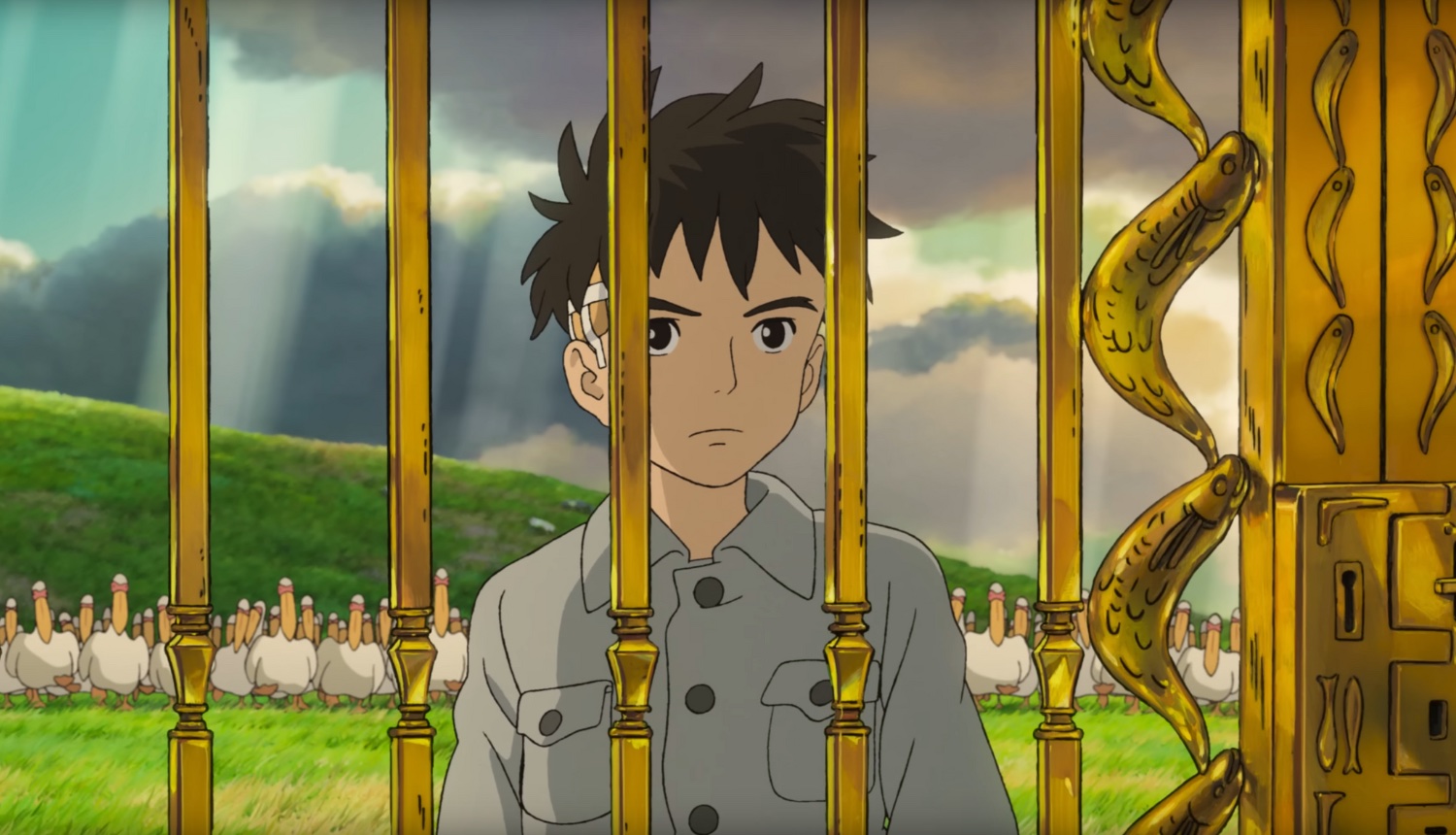

Hayao Miyazaki's THE BOY AND THE HERON

Master of animation Hayao Miyazaki has claimed he’s retiring before, but the Japanese artist – who co-founded world renowned animation house Studio Ghibli in 1985 – has once again returned to the big screen with one of his most personal and gorgeously intricate films The Boy and the Heron.

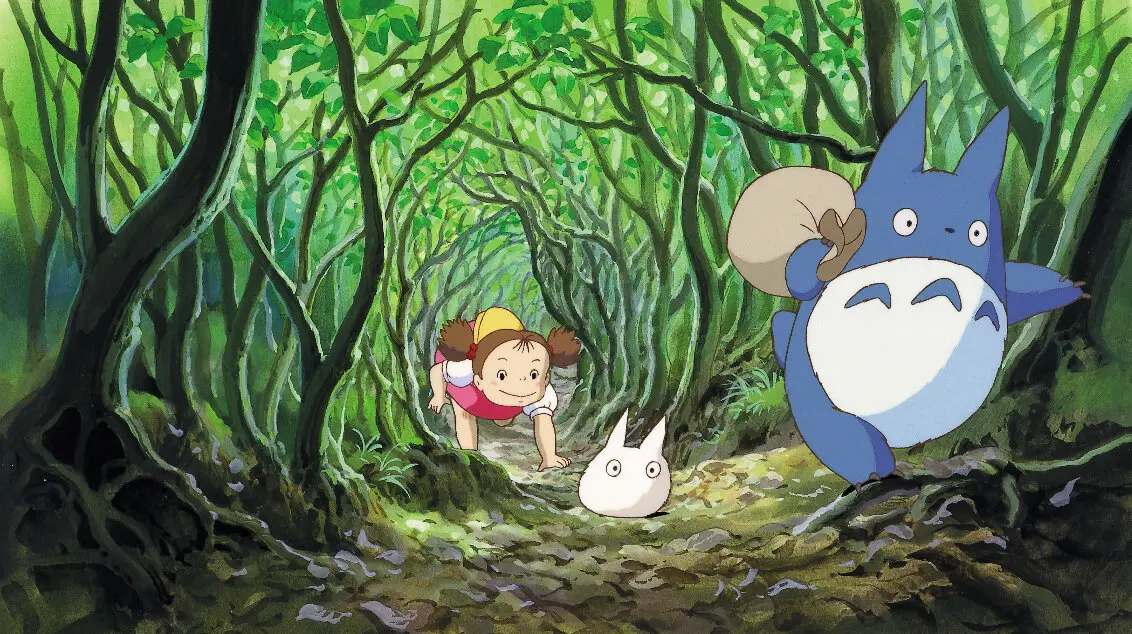

The octogenarian’s creations never cease to push the boundaries of imagination, and Heron is no different. Tender, beautiful, macabre, thoughtful, hilarious, and heart-wrenching all at once, all of Miyazaki’s films – from the indelible fuzzy spirits in My Neighbor Totoro (1988), to the epic fantasy tale Princess Mononoke (1997), to the contradictions of love and war in Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), to the lovable and enchanting Ponyo (2008), to one of the highest-grossing film in Japanese history and Oscar-winning Spirited Away (2001) – continue to contribute to the ever-expanding, rich Miyazaki mythology.

Nearing the end of his tremendous career of phenomenal achievement, the world reflects on how Studio Ghibli broke through, what is like to work with him, and how he became one of the most treasured legends in animation and film lore.

In 2021, the New York Times profiled Miyazaki as he prepared to work on The Boy and the Heron:

The screen is black, and then comes the first frame: Hayao Miyazaki, the greatest animated filmmaker since the advent of the form in the early 20th century and one of the greatest filmmakers of any genre, is seated in front of a cast-iron stove with a pipe running up toward the ceiling, flanked by windows propped half open. Sun burns through the branches of the trees outside. Three little apples perch on a red brick ledge behind the stove. He wears an off-white apron whose narrow strap hooks around the neck and attaches with a single button on the left side — the same style of apron he has worn for years as a work and public uniform, a reminder that he is at once artist and artisan, ever on guard against daubs of paint — over a crisp white collared shirt, his white mustache and beard neat and trim, and his white hair blurring into a near halo as he gazes calmly at me through owlish black glasses, across the 6,700 miles from Tokyo to New York.

I have one hour to ask questions. It is a rare gift, as Miyazaki has long preferred not to speak to the press except when absolutely necessary (which is to say, when he’s prodded into promoting a film), and has not granted an interview to an English-language outlet since 2014. Our conversation has been brokered by the newly opened Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles, which mounted the first North American retrospective of his work in September, with Studio Ghibli’s cautious assent; Jessica Niebel, an exhibitions curator, cites him as an exemplar of an auteur who “has managed to stay true to himself” while making movies that are “approachable to people everywhere.” I know I am lucky to have this time, and yet it feels wrong to meet Miyazaki this way, at a distance (due to Covid-19 travel restrictions) and through a computer, a machine he has so famously shunned.

Read Ligaya Mishan’s full New York Times profile on Miyazaki here.

Prior to The Boy and Heron‘s release, The Ringer investigated how Miyazaki transferred Studio Ghibli’s success in Japan to a worldwide phenomenon:

In 1984, Hayao Miyazaki’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind premiered in Japan. Based on the manga that Miyazaki had started two years earlier for Tokuma Shoten’s Animage magazine, Nausicaä was only the second feature of Miyazaki’s animation career. It’s a remarkable film that earned critical acclaim and commercial success, but the company that produced the film, Topcraft, went out of business soon after its release. Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, who was something of a mentor to Miyazaki and also the producer of Nausicaä, were already widely respected veterans of Japan’s animation industry. Yet no production company was willing to take on the costs of their next film. And so, along with producer Toshio Suzuki, they started a company of their own: Studio Ghibli.

Studio Ghibli was thus born out of necessity. For Miyazaki and Takahata, founding the studio was a crucial step toward achieving the independence they craved, as parent company Tokuma Shoten largely left Ghibli to its own devices. Until then, the animation auteurs had been held back only by the limitations of their era, forced to work within the traditional confines of a medium that still struggled to escape the boundaries of TV. Together, with the business savvy of Suzuki to guide their works to prosperity, Studio Ghibli would forever change the world of animation.

In 1995, 10 years after Ghibli’s creation, Suzuki delivered a speech at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival in which he reflected on the studio’s original mission: “Ghibli’s goal has been to devote itself wholeheartedly to each and every film it has undertaken, not to compromise in any way whatsoever. It has done this under the leadership of directors Miyazaki and Takahata, and by adhering to the tenet that the director is all-powerful. The fact that Ghibli has somehow been able to maintain this difficult stance for 10 years, to realize both commercial success and proper business management, is due to the exceptional ability of these two directors and the efforts of the staff. This can be said to be the history of Studio Ghibli. To make something really good, that was Ghibli’s goal. Maintaining the existence of the company and seeing it grow were secondary considerations. This is what sets Ghibli apart from the ordinary company.”

Read the Daniel Chin’s full story on Miyazaki lore here.

In a recent New York Time’s piece, Toshio Suzuki, a founder of Studio Ghibli and Miyazaki’s right-hand man for the past 40 years, talks about what it’s like to work with the famed animator:

For a long time, he said, Miyazaki worried that if he made a movie about a young male, inspiration would inevitably be drawn from his own childhood, which he felt might not make for an interesting narrative. Growing up, Miyazaki had trouble communicating with people and expressed himself instead by drawing pictures.

“I noticed that with this film, where he portrayed himself as a protagonist, he included a lot of humorous moments in order to cover up that the boy, based on himself, is very sensitive and pessimistic,” Suzuki said. “That was interesting to see.”

If Miyazaki is the boy, Suzuki added, then he himself is the heron, a mischievous flying entity in the story that pushes the young hero to keep going. The director Isao Takahata, Studio Ghibli’s third foundational musketeer, who died in 2018, is represented onscreen by Granduncle, a wise but weathered figure who controls the fantastical world Mahito ventures into.

Suzuki first met Miyazaki in the late 1970s, when the animator was making his first feature, “Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro,” an amusing caper. Back then, Suzuki was a journalist hoping to interview him. But Miyazaki, who was working on a storyboard, had no interest in talking and ignored him. “Out of kindness, I thought it was a good thing to introduce his works to my readers, and for him to be very cranky and disrespectful, I was very angry,” Suzuki remembered.

He stuck around the studio for two more days of silence. On the third, Miyazaki asked him if he knew a term for a car overtaking another during a chase. Suzuki’s reply, a specific Japanese expression for such action, finally broke the ice and kick-started their long-term relationship.

“Miyazaki still remembers that first meeting, too,” Suzuki said. “He thought that I was a person not to be trusted. And that’s why he was very cautious about talking to me.”

The article also explores Miyazaki’s very unique relationship with composer Hisaishi:

In contrast, Hisaishi, the composer who first worked with Miyazaki on the 1984 feature “Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind,” has a strictly professional relationship with him.

“We don’t see each other in private,” Hisaishi, wearing an elegant sweater, said through a translator. “We don’t eat together. We don’t drink together. We only meet to discuss things for work.” That emotional distance, he added, is what has made their partnership over 11 films so creatively fruitful.

“People think that if you really know a person’s full character then you can have a good working relationship, but that doesn’t necessarily hold true,” Hisaishi said. “What is most important to me is to compose music. The most important thing in life to Mr. Miyazaki is to draw pictures. We are both focused on those most important things in our lives.”

Read more of Carlos Aguilar’s story about Suzuki and Hisaishi’s relationship with Miyazaki here.