The Lubitsch Touch

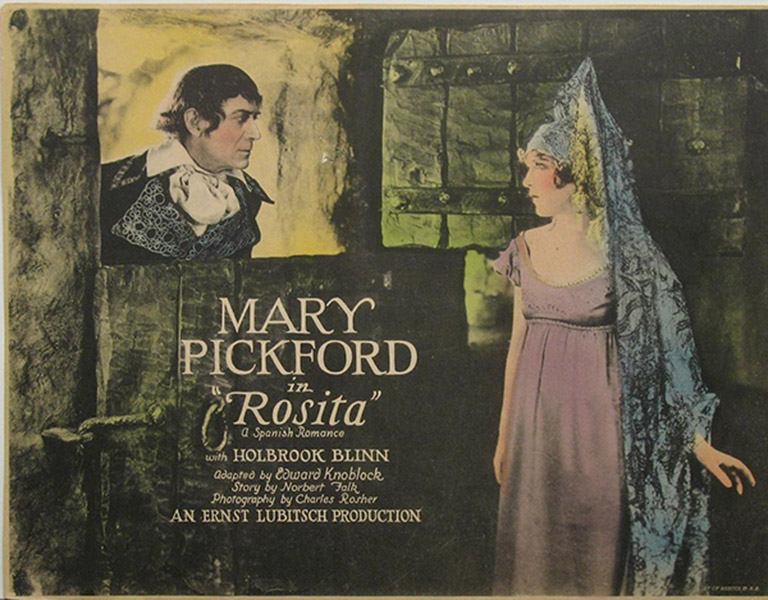

Following The Film Foundation and MoMA’s 2018 restoration of Rosita, J. Hoberman said in a New York Times review, “There are films that are lost or so deteriorated that they take on the quality of a holy grail. ‘Rosita’ (1923), the first American movie by the German director Ernst Lubitsch, is one.”

We will be playing that holy grail as a part of our Festival of Preservation with an introduction from MoMA’s Film Curator, Dave Kehr. This kind of restoration is likely what comes to mind for most people when they hear “preservation,” as written about by the UCLA archives:

Rosita was digitally restored in a two-year process from a 35mm dupe acetate negative, made in the 1960s from a nitrate print that had survived in the Soviet Union. Also scanned was a missing reel of 10 minutes, previously unseen in the 16mm print downs in circulation. The images were cleaned up and tinted digitally, dramatically improving the viewing experience of the film. New English-language intertitles were reconstructed from the translated Russian titles, augmented by texts from the Swedish and German censorship records, while the style was copied from the single reel of Rosita, preserved by the Mary Pickford estate. A new score was created by musicologist Gillian Anderson from original music cue sheets that survive at the George Eastman Museum. Watching the film, I realized that Rosita has not only been undervalued by film historians—probably due to the lack of access—but it is also a major work that really ties together Lubitsch’s historical epics in Germany with his romantic American comedies.

This 2018 restoration provided access to the film for the first time since its original release. Read the full piece from the UCLA Archives here.

Filmmakers from the early days of Hollywood have long cited Lubitsch and as one of the most defining figures of modern cinema. A.O. Scott wrote an article on “the Lubitsch touch” for The New York Times, opening with this anecdote:

A famous sign on the wall in Billy Wilder’s office asked, ”What would Lubitsch have done?” Wilder meant the question as a tribute to Ernst Lubitsch, his master, mentor and sometime boss — a comic filmmaker whose elegant and effortless command represented, to Wilder and many others, the apogee of cinematic wit, sophistication and technical precision.

Peter Bogdanovich was massively influenced by Ernst Lubitsch, even using a reference to one of his films as a title: Squirrels to the Nuts, which will be playing on Saturday in our Festival of Preservation with an introduction from James Kenney, a CUNY professor who found Bogdanovich’s cut of the film on eBay and, thus, saved the “Lubitsch cut” from peril — a less obvious form of film preservation. Bogdanovich wrote an article about Lubitsch for The Observer, in which he tells another powerful anecdote to open his argument:

Sometime in the late 1960’s, I asked Jean Renoir what he thought of Ernst Lubitsch. He raised his eyebrows and said, enthusiastically, “Lubitsch!? But he invented the modern Hollywood.” By “modern Hollywood,” Renoir meant American movies from about 1924 to the start of the ’60s. Before Lubitsch’s arrival to California from Germany in 1922 (to make a Mary Pickford vehicle called Rosita), Hollywood films were under the overwhelming influence of D. W. Griffith, circa 1908 through the epoch-making The Birth of a Nation in 1915 and beyond. Victorian, puritan, Southern, montage-driven, Griffith was the father of film narrative. As pioneer Allan Dwan told me, he would go to see Griffith’s movies and just do whatever Griffith was doing. The majority of American directors felt similarly, including John Ford and Howard Hawks.

When Lubitsch arrived, however, things started to change. He brought European sophistication, candor in sexuality and an oblique style that made audiences complicit with the characters and situations. This light, insouciant, teasing manner became known far and wide as “the Lubitsch Touch.” By the end of the 20’s and throughout his short life—he died in 1947 at age 55—Lubitsch was probably the most famous film director internationally, except perhaps for C. B. DeMille. Today hardly anyone remembers either one of them. Yet while most of DeMille is pretty forgettable, if sometimes fun, Lubitsch is always fun and often as good as it gets.

Bogdanovich’s full article, which is really worth a read beyond these two paragraphs, is available here. He also goes on to say this:

Naturally, all older films suffer from not being seen, as they were meant to be, on the big screen, which is probably one of the main reasons why younger people are so impatient with anything made earlier than about 1990. I was fortunate to have first seen these Lubitsch musicals in a large screening room at Paramount in the mid-1960’s when Jerry Lewis generously set me up to screen whatever studio prints I cared to run. I ran 82 movies, some in their original, gloriously shimmering nitrate prints. There is simply no substitute for that. We cinéastes of the 60’s used to scoff when someone said they had only seen a classic on TV: “Then you haven’t seen it,” we’d say. Now it’s all on TV, and there’s very little chance of viewing classics the way they were meant to be seen (Film Forum and MoMA are two New York oases).

The Mary Pickford Foundation recounts the way Pickford was responsible for Lubitsch making it to Hollywood in the first place, specifically choosing him to help her make her first appearance as an “adult woman” in Rosita:

Pickford had seen Lubitsch’s German films and was impressed. As she recalled in a 1958 interview with George Pratt, “I had already done the second Tess of the Storm Country and I wanted to do a grown-up role. I wanted to do an adult woman.” And she thought a director such as Lubitsch would have the “touch” to do that successfully.

But first she had to get the director to Hollywood and the American Legion, amongst others, objected vociferously. Pickford recalled to Kevin Brownlow in 1974 that she was on stage when the head of the American Legion took to the podium to say: “I hear that the Son of the Kaiser is coming here. He doesn’t belong here, he is still our enemy. Why are they bringing German singers over here? Do we not have good enough singers here in the United States, without going to Germany?”

Pickford’s response: “General. Since when has art had borderlines? Art is universal. And for my pictures, I will get the finest, no matter what country they come from. The war is over. And it’s very ill bred and stupid for the general to stand up and talk like that. A German voice is god given if it’s beautiful. Yes, I am bringing Mr. Lubitsch over here and I’m glad I can.”

Pickford, who appreciated her power yet was careful about how she used it, had stood up for what she thought was right. Still, the woman who had put her career on hold to tour the country and sell millions of dollars in war bonds said she found herself being denounced as a traitor for ignoring our own directors in favor of the erstwhile enemy.”

Their entire article about Lubitsch, Pickford and the making of Rosita is available to read, here.