George Stevens' GIANT film

Clocking in at a whopping three and a half hours, George Stevens’ adaptation of Edna Ferber’s novel of racial tension and Texan oilfields lives up to its Giant name. With the star power of Elizabeth Taylor, Rock Hudson and James Dean, in what would be his final role, under the direction of one of the great American filmmakers, Giant boasts influence on the likes of Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg.

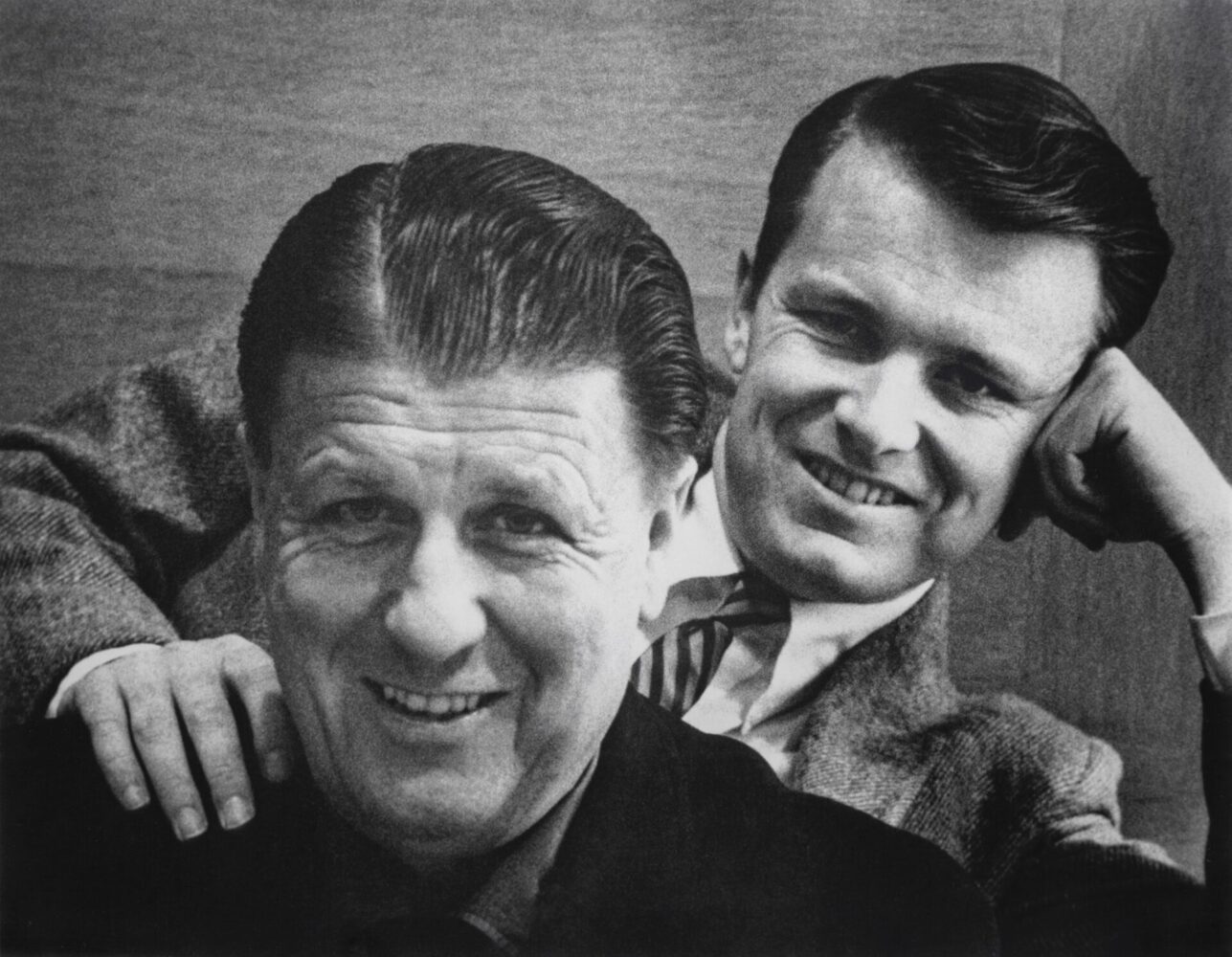

Sag Harbor Cinema will host a screening of the 4k restoration of Giant, introduced by George Stevens Jr., who was onset of the film with his father and served as a production assistant on several of his films.

Courtesy of George Stevens Jr.

Peter Tonguette writes in Sight and Sound, BFI’s international film magazine, that Giant was an epic as weird as it was ambitious in a 2016 article:

A decade before tackling Giant, Stevens had famously altered the course of his career, forsaking the mild comedies he had specialised in – including Swing Time (1936), Woman of the Year (1942) and The More the Merrier (1943), all delightful – for more serious, solemn scripts. Even so, there is nothing in the ensuing batch of dramas to suggest the scale of Giant. To be sure, I Remember Mama (1948) and A Place in the Sun (1951) are important films, but epics they are not. Giant, then, is sui generis. Its staggering size not only does justice to Texas but also provides room for subplots and detours; the film is simply loaded with incident. “When you do this,” Stevens said in a 1973 interview at the American Film Institute, “the essential thing is to make sure you’re telling a story.” Beyond detailing the eventual marriage of Bick and Leslie, the film follows the progress of their children – played as adults by Dennis Hopper, Carroll Baker and Fran Bennett – as well as the providence-filled saga of Jett Rink (James Dean), a ranch hand in the employ of Bick who has an unlikely second act as an oil magnate.

The length of Giant also allows for the inclusion of odd touches likely to have been omitted in a tighter cut. Mere minutes into the film, Stevens introduces a curious technique which is deployed throughout the film: the director uses dissolves within single scenes. As Bick waits for Horace at the train station in Maryland, the camera is initially positioned low to the ground and moves in on the Texan’s boots. Then, unaccountably, Stevens dissolves from this shot to a wider angle of Bick in the same position; because no appreciable time has passed, it’s the cinematic equivalent of turning the page in a book mid-paragraph.

Here, at least, there is some precedent. In an equally mystifying moment in Stevens’ western Shane (1953), Jack Palance swings open the doors to a saloon, but before he can walk in, the film skips ahead; Stevens dissolves to a shot of Palance moving past the camera. This choice utterly flummoxed one of the film’s biggest fans, Woody Allen. “It’s one of the most puzzling dissolves I’ve ever seen,” Allen said in a 2001 interview about the film in the New York Times. “I can’t imagine what it was for. It must have been to cover up a mistake.” Or – on the basis of the use of the same technique in Giant – not.

Like his successors Altman, Cimino and Malick, Stevens uses his film’s length indulgently – pausing for passages of pure poetry. For example, at the end of his stay in Maryland, Bick follows Leslie to a white picket fence – soon joined by the horse Bick now owns. Bick and Leslie gaze at each other without speaking. Then, in a thrilling moment, Leslie turns her head from Bick while the camera pans past her and tilts up to the canopy of a tree; here, one could argue, is the unlikely source of Altman’s wandering camera. The drama of the pan is pleasing in itself, but it also implies that something significant is about to transpire – and indeed it does. In the next scene, Bick and Leslie are revealed to be newlyweds as they share a compartment on a train headed to Texas.

Read the rest of the article here.

Giant was restored earlier this year with the support of TCM and The Film Foundation. Steven Spielberg introduced the premiere of the restoration at the 2022 TCM Classic Film Festival:

“Anything that presumes to call itself ‘Giant’ better have the goods to keep such a lofty promise,” Spielberg said in a press statement. “Both (author) Edna Ferber and (director) George Stevens far exceeded the title to bring such an epic American story to the big screen and I’m proud to have been a small part of the restoration team of this classic motion picture.”

The film received 10 Academy Award nominations and is noted for exposing the marginalization and segregation of Mexican Americans for one of the first times on the big screen.

The new 4K restoration was completed sourcing both the original camera negatives and protection RGB separation master positives for the best possible image, and color corrected in high dynamic range for the latest picture display technology. The audio was sourced primarily from a 1995 protection copy of the original magnetic mono soundtrack. The picture and audio restoration was completed by Warner Bros. Post Production Creative Services: Motion Picture Imaging and Post Production Sound

Full article available here.

Below is the original theatrical trailer for Giant from the Texas Archive of the Moving Image:

If you are having issues seeing the video, click here to watch it on the Texas Archive website.