Canyon Passage was never the film synonymous with its director Jacques Tourneur, who was more widely recognized for his horror and film noir (i.e. Cat People). Film critic Chris Fujiwara discusses his view that all of Tourneur’s films were interesting, but that he was often overlooked as a French director, particularly in an American-centric genre:

The history of how Tourneur was appreciated is a little particular.

A lot of the Hollywood directors were championed by writers like Manny Farber and later by Andrew Sarris, so that’s how people like Don Siegel, Samuel Fuller, Anthony Mann, all of these directors were discovered and pretty much established as auteurs, not just in France, which had made the initial discovery, but also in the United States and in the UK.

That had happened by the sixties, but Tourneur had been somewhat passed by, even a little bit in France although by the late sixties, thanks in part to Pierre Rissient and other people, Serge Daney, Tourneur was beginning to be better known and people were starting to write about him.

Even in the nineties, Tourneur was not a forgotten figure but a somewhat neglected one. There was a retrospective of Tourneur at the Edinburgh Film Festival in the 1970s, I think 1975, there was a short book published in connection with that. There was some awareness of Tourneur but, as I said, there hadn’t been a real book in English. So I thought, this is an interesting thing, I would like to work on this. I originally thought that I would put it in the context of other European directors who were working in the United States in the so-called classical period of Hollywood cinema, Fritz Lang, Jean Renoir. But then I decided to do just Tourneur and I’m glad I did.

On Canyon Passage, Fujiwara says, “I value his westerns very much, Canyon Passage is one of his masterpieces.”

Full interview available here

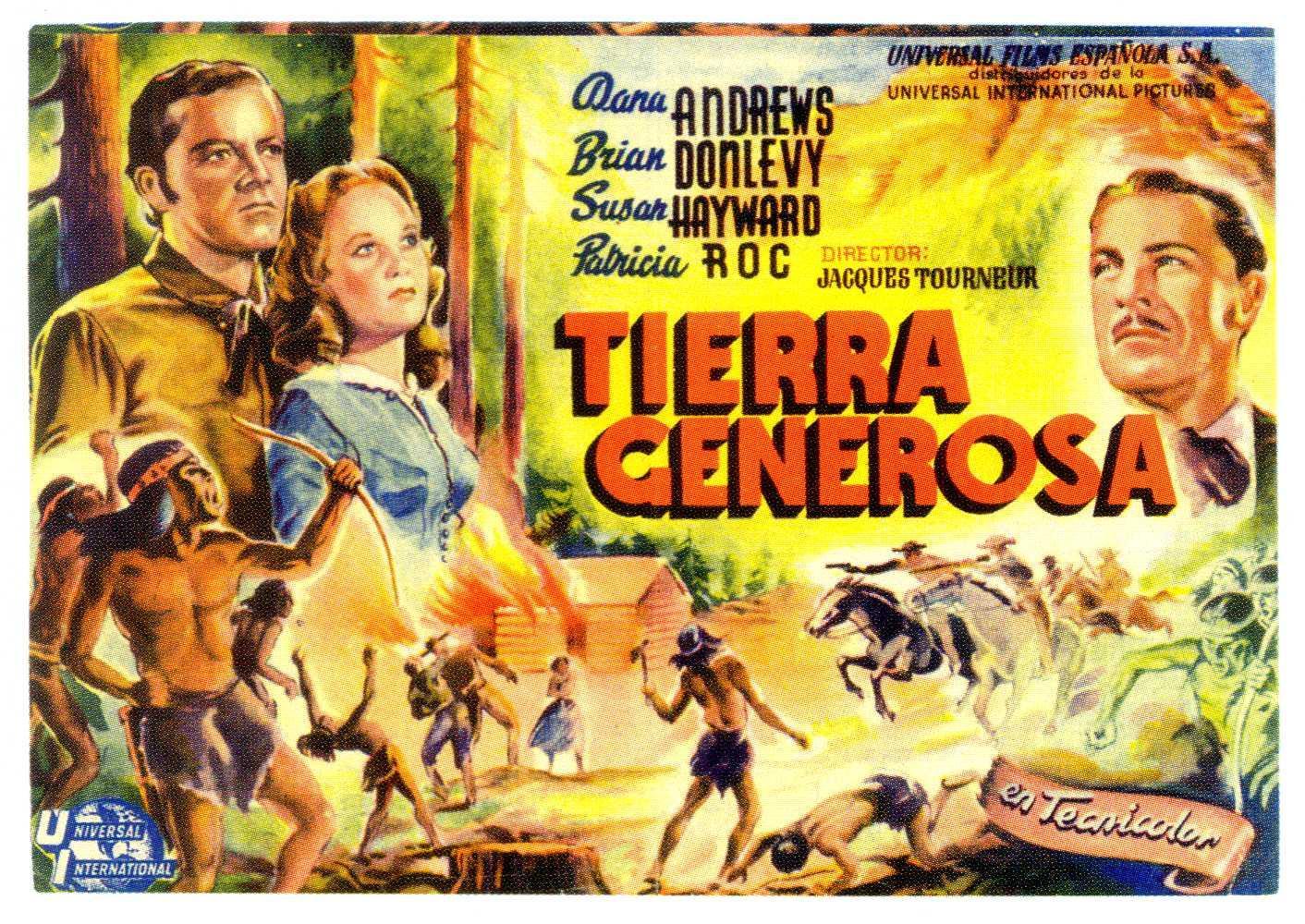

One of Canyon Passage’s international posters

While Canyon Passage, a story of the Oregon frontier, is a Western, it stands out from traditional films of the genre both narratively and aesthetically, as Michael Barrett explains:

In theory, the film’s a western. In practice, it feels more like Americana, as founded on a subtle, incidental, expansive script by Ernest Pascal from Ernest Haycox’s novel. Not much happens for most of the movie except the image of a small community peopled by many figures who enter and exit the frame and the narrative in a complex web of relations, uttering philosophical remarks like “The illusion of peace is upon it” (George) and “A man can choose his own gods” (Logan). All this to-ing and fro-ing is shot by Edward Cronjager in Technicolor arrangements that show off Tourneur’s often stunning pictorialism. If we’re not staring at vistas of mountains, lakes, and forest, we’re luxuriating in interiors of many colors, tones, and textures.

In his introduction to Chris Fujiwara’s Jacques Tourneur: The Cinema of Nightfall (1998), Martin Scorcese says Canyon Passage is very special to him, “one of the most mysterious and exquisite examples of the western genre ever made”. Fujiwara calls it “another of Tourneur’s neglected masterpieces and one of the greatest westerns”. Scorcese points out that the film has no plains or deserts, and Fujiwara that it conforms to none of the standard western models: revenge story, journey story, outlaw story, cavalry story, “nor primarily a story in which the hero tames the town or accomplishes some difficult feat”.

Read the full article, here.

The New York Times review from the initial release of the film describes Tourneur’s first foray into Technicolor as, “Miles of beautiful outdoor scenery in stunning Technicolor is lavishly punctuated with rough and tumble episodes, moments of tender romance and a smattering of folk customs, circa 1856, when adventurous pioneers were struggling against nature and hostile Indians to make their fortunes in the Oregon country. Almost every type of familiar character one might expect to encounter in a sagebrush melodrama is on hand.”

Richard Brody later described it for The New Yorker as, “utterly contemporary; avoiding history and politics, Tourneur serves up, in a dreamlike Technicolor glow, a pastoral film noir.”

A promotional photo from Universal

Perhaps one of the reasons that Canyon Passage was overlooked by the Academy when it was released, not counting the nomination for “Ole Buttermilk Sky” from the soundtrack, was the unconventional take on the Western that Tourneur brought to the film. There are many instances where his auteurist mentality created friction with producers, who believed they knew Technicolor better. Tourneur was not the first choice to direct, but fresh from his success with Cat People and I Walked with a Zombie, he brought a fresh perspective to the classic American Western:

Much of the filming was new territory for Tourneur. A second unit, unusual for Tourneur, directed by Charles Barton was employed, mainly for the house-raising, but was also for some action scenes. Tourneur said of this decision: “I’ve always fought second units. Whenever I have any control at all I just don’t have them.”

Walter Wanger kept a close eye on production, concerned that the film would be brought in on budget, and became concerned about the lack of closeups: “ … Looks very good with exception lack of closeups of leads which necessary to carry story. Without closeups Technicolor looks like scenic …” he wired Tourneur. To cinematographer Edward Cronjager, he also wired: “Quality excellent however very worried about lack of closeups of leads as we are losing story points.” Wanger expanded on these comments saying that more closeups were needed in Technicolor than black and white so that characters and expressions don’t fade into the background, losing scenery and story points.

Tourneur replied: “Will have so many closeups of cast in studio interiors and street for seventy five percent of story so we will all be glad of relief of medium shots in the few exteriors we do have. Aside from that I disapprove of closeups except when I reach story points.”

After Tourneur made some concessions to Wanger, at least one of which, a scene with Dana Andrews and Ward Bond, ended up on the cutting room floor, filming progressed.

Much of Canyon Passage is told in Tourneur’s gothic imagery. Night scenes abound with wonderfully lit Technicolor photography by Cronjager. Violence is Implied: George Camrose (Brian Donlevy) marches menacingly to the river, about to drown a miner whose gold dust he has pilfered; The brutal Honey Bragg (Ward Bond) conveniently falls behind a log to be scalped by an Indian; a mound of straw conceals the killing of a young mother, trying to escape from Indians with her baby – a raised tomahawk-wielding hand says enough.

Read the rest of this excellent blog post, here.